CERN’s large hadron collider

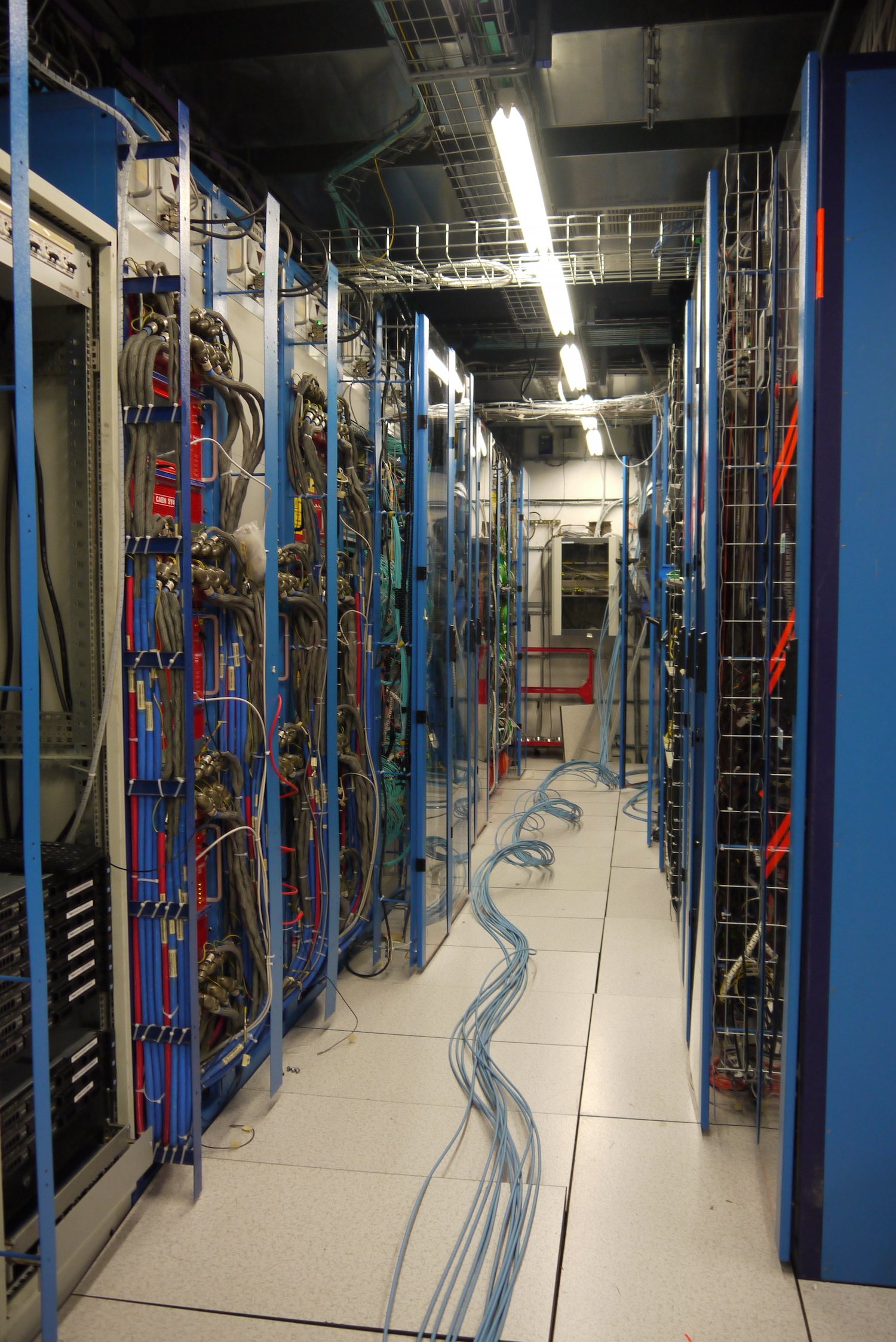

A few basics: CERN stands for the European Organization for Nuclear Research, although the name does little to convey the scope of the work, which today focuses on particle physics. Physicists and engineers from around the globe build and monitor experiments to investigate the structure of the universe. The large hadron collider (LHC) is a 27-kilometer ring of superconducting magnets that guides particles around and around until they reach close to the speed of light. They then smash together in collisions that are photographed (40,000,000 pictures per second!) and analyzed in an effort to learn more about how particles interact, and shed light on how the universe works.

I didn’t go to CERN with the idea that what I learned about physics would feed directly into the artwork I am doing focused on genetics and mutation—but I was open to finding connections. I had a sense that viewing my current project through the lens of particle physics could be a way of opening it up for growth in new directions. I’d long dreamed of visiting the LHC—could it possibly live up to my expectations? I had doubts. I was excited, but also nervous to see the Compact Muon Solonoid (CMS) experiment connected to it—a 15-meter high particle detector (basically a giant camera)—in situ. I am claustrophobic and purposefully journeying 100 meters underground?! What was I getting myself into? And apart from seeing the experiment, what else would CERN have to offer up?

I’ve been experimenting with audio recording in London, and brought me recorder to Switzerland. This is a new medium for me, and I had no plan for it at CERN nor ideas for what I’d do with it after the visit (although that is evolving now). But the act of the recording allowed me to experience the trip in a unique way. With each session or visit, I’d push Record, but take very few photographs and make few written notes. I quickly settled into simply being present, experiencing the lectures, the site visits, the broader space. As if the audio recordings took the place of a more concrete intellectual or visual documentation and allowed me to engage with the experience in a more sensory and abstract way.

What didn’t get recorded is as important as what did. I had the recorder switched on for the build-up and descent to see the CMS experiment, but have no recording for the time spent in the cavern on the viewing platform across from the particle detector—the one thing I knew I wanted to see. As a group, we didn’t speak much while in the cavern. Did we? The experiment wasn’t running, but I have a sense that there was a lot of white noise. Was it loud? I can’t quite recall. I had a hard time imagining the invisible collisions that would take place inside the giant, colorful particle detector. But I was aware of the history of the space as I stood there, of the manpower and passion required to construct the experiment; and of my own history—a longing to share this with my deceased father, a physicist and engineer who would have loved to have visited CERN. Were we as reverent in the cavern as my memory implies? Is that why I didn’t press Record—did the essence of a collective human spirit, the detector, or even the earth’s cavern dictate my actions?

As a nonscientist, I had daydreamed about the visual appeal of CERN (the visible and invisible). And the LHC, the enormous experiment involving particles too small in scale to see but whose collisions generate massive amounts of data aimed at addressing immense (almost philosophical) questions. My mind was on the objects of study, not the people who study them. But over the course of our four days visiting CERN, interacting with physicists and learning about CERN’s history, I began to wonder, can we separate the science from the humans directly investigating it?

So particle physics, the search for the origins of the universe, the visual appeal of the particle detector both as an object and as a camera illuminating the invisible—these are the things that initially drew me to CERN. But what I left with, along with an introduction to the science and technical tools used in the research, was a sense of the tens of thousands of hands and hearts and minds that have driven the science forward, melding passion and patience with the invisible nature of the undiscovered until something new emerges, a combined effort of man and nature giving birth to greater understanding.

On our final evening, one of our guides arranged for me to meet a physicist who was involved in work related to some of the medical applications of technologies coming out of CERN’s work. This meeting was a second highlight of the trip, was particularly meaningful to me. My (unrecorded) conversation with this physicist, standing in the canteen with small plastic cups of wine in our hands, directly linked my explorations in science to hers and CERN’s; linked my personal story to hers as two unique human beings coming together from a place of curiosity and of openness. An unexpected exchange. A second reverent experience. Linked as much to the individuals as the science starting the discussion.

The science cannot be separated from the individuals who are working within it. Part of CERN’s mission is to explore the origins of the universe, answering questions about where we come from and what we are made of; medical science and the study of the genome (my area of focus on the MAAS course) does the same. The science involves discourse engaged with data, numbers, chemicals, particles. But the outcome is about humans and humanity, and the individuals driving this search are as important as the knowledge coming out of it.

UPDATE MARCH 2017:

In May I returned to CERN with a small group of students for some follow-up research. I got so much out of the 3-day visit: visiting several CERN experiments like the CMS and the cloud experiment; a personal visit with Knowledge Transfer Group team members working on an improved PET scan for breast cancer (The Knowledge Transfer Group’s mission is ‘to optimize the impact of CERN’s science, technology and know-how on society’); participating in a roundtable discussion between artists and esteemed CERN scientists, to explore the common ground shared by the two fields. This was an opportunity to build confidence around speaking about my art practice and art & science; attend fellow students’ art workshops; and enjoy an evening wandering the site with Olga Suchanova as we played with pinhole photography. I met with two established artists who have or are working on art-science collaborations, and it was really inspiring to think about how my practice could develop over the coming years. This second trip was a great opportunity to develop the interests and relationships we started as a group last December, and to work toward a collaborative dialogue that flows both ways.